An Osprey known as ‘09’ satellite-tracked from Rutland in England spent the last winter in Senegal (so he already has experience in desert crossing). His autumn migration this year was cut short by an avian or mammalian predator while he was roosting on the northern edge of the Sahara in southern Morocco.

This story is written by Tim Mackrill and was

originally published in the Rutland Osprey Project’s website before they delete

it.

|

| Osprey’ foot and feathers and the colour ring (Farid Lacroix). |

Introduction

Last week when I put out an appeal on the

website and e-mailed some contacts in Morocco, it was more in hope than

expectation that someone in Morocco may be able to go and find out what had

happened to 09(98) on the edge of the Sahara. We were receiving transmissions

from a remote ridge of the northern edge of the desert, well away from main

roads and in some of the most inhospitable terrain in Africa – or perhaps, more

accurately, the world has to offer. Surely, 09’s fate would remain a mystery?

Well, not when you have Farid Lacroix to help you. Farid is an ex search and rescue helicopter pilot, originally from France but now living in Agadir, in the south of Morocco. Farid’s career has taken him all over the world, and most significantly of all from our point of view, into the desert. When he saw our appeal for help on moroccanbirds.blogspot.com, he immediately got in touch and offered to drive the 250 km from Agadir to the spot where we had been receiving transmissions from 09’s satellite tag since 3 pm on September 11th.

The Sahara is not the sort of place you can take lightly – conditions can

suddenly deteriorate in a matter of minutes – but Farid’s experience meant he

was well-qualified to deal with the worst the desert could throw at him.

Farid’s trek into the Sahara

So, on last Thursday morning, Farid left

Agadir and drove south. Leaving the main roads behind, he headed onto dirt

tracks and into the desert. Using his Garmin GPS as a guide he eventually

reached the foot of the mountain where the satellite data showed 09’s tag was

lying.

In Farid’s own words, ‘climbing this mountain was very hard and maybe dangerous’. That was an understatement, but unperturbed he set off up the mountain with a 15 kg rucksack containing 3 litres of water, some food, a survival blanket, a satellite phone in case of an emergency and his camera equipment.

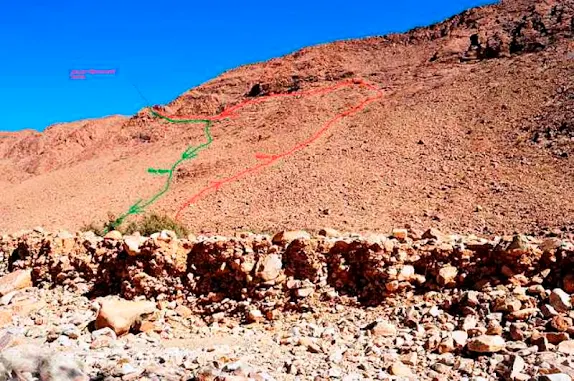

The photo below shows his route up the

mountain, which involved more than 1000 feet (305 m) of climbing on loose

shale. This would be difficult enough on its own, but the searing desert

temperatures made the climb even more demanding.

|

| Farid’s routes up (red) and back down (green) the mountain ridge where the Osprey died. |

The Osprey predated by an avian or mammalian predator

So, sadly we now knew 09’s fate, but what was it that killed him? A look at data from his transmitter’s activity meter suggests he was alive until the early hours of 12th September and, therefore, it seems likely he was predated by either a Pharaoh Eagle Owl or a mammal, perhaps an African Golden Wolf, during the night or very early next morning. This theory is given more credence by the fact that Farid found 09’s remains a few feet from the branch where he would have been roosting; tell-tale white excrement suggesting he had been perched there for some time. Perhaps conditions in the desert were poor for migrating on the afternoon of 11th September, forcing 09 to cut-short his day’s flight? Sadly it seems that it was this decision to roost on the ridge that resulted in his demise; an owl or mammal pouncing on him in the night and then eating him where Farid found the remains.

It certainly seems very unlikely that he died of natural causes.

Having flown more than 250 miles on each day of his seven-day flight to

southern Morocco, he was clearly in good condition.

Of course, we will never know exactly what

happened, but whatever the case, it goes to show that even for an experienced

Osprey, like 09, migration is a very hazardous time. The desert terrain means

that migrating Ospreys have to roost on or very close to the ground, making

predation a very real threat.

|

| Osprey’ bones and the satellite transmitter (Farid Lacroix). |

Linking people and communities

We are incredibly grateful to Farid for going to such amazing lengths to find out what had happened. It is remarkable that someone we have never met offered to drive 500 km and scale a 1000-foot mountain in the Sahara to help us solve the mystery.

As I said in the previous post, migrating birds have a unique ability to link people and communities across the world, and this is a perfect example of this. We are currently setting-up a project that will link schools along the Osprey migration flyway and I hope that this will encourage young people in Europe, Africa and perhaps further afield to follow Farid’s example and to take an interest in the conservation of migratory birds.

As 09’s sad demise shows, Ospreys and other

migratory species face many natural hazards on their 3000-mile journey to

Africa, and I feel it is vital that we do all we can to encourage international

collaboration and partnerships to ensure that those threats do not include

human ones.

Thank you again, Farid.

Comments

Post a Comment